The superorganism is a scientific topic, so readers may wonder why this appears on a website concerned with politics. The reason is that my next political article will be on the topic The Role of the Citizen in a Spiritual Society, and as a prelude to that, in my next article, I intend to address the question whether humanity, or even more controversially the Earth, is a superorganism. I therefore want to clarify what exactly is meant by the term, and provide relevant background information. The article is a little long; I hope you’ll stay with it – those readers who are interested in the debate surrounding materialist science should find it informative.

A primary source for what follows is The Lives of a Cell by Lewis Thomas (1). He explains that by superorganism is meant “the idea that colonies of social insects (he is talking about ants and termites) are somehow equivalent to vast, multicreatured organisms, possessing a collective intelligence and a gift for adaptation far superior to the sum of the individual inhabitants (2)”. “Collective intelligence” is the key phrase; a paraphrase would be “group mind”. In the words of F. David Peat: “the single insect… carries within it, in some hidden or enfolded fashion, the behaviour of the hive or the colony (3)” (my italics – in what follows all italics are mine, unless otherwise stated).

Here are some statements which suggest that we should take this concept seriously:

“Ants are more like the parts of an animal than entities on their own. They are mobile cells, circulating through a dense connective tissue of other ants in a matrix of twigs. The circuits are so intimately woven that the anthill meets all the essential criteria of an organism (4)”.

“Somehow, by touching each other continually, by exchanging bits of white stuff carried about in their mandibles like money, they manage to inform the whole enterprise about the state of the world outside, the location of food, the nearness of enemies, the maintenance requirements of the Hill, even the direction of the sun. … The Hill, for its part, responds by administering the affairs of the institution, coordinating and synchronizing the movements of its crawling parts, aerating and cleaning the nest so that it can last for as long as forty years, fetching food in by long tentacles, rearing broods, taking slaves, raising crops, and, at one time or another, budding off subcolonies in the near vicinity, as progeny (5)”.

“…but if you think about the construction of the Hill by a colony of a million ants, each one working ceaselessly and compulsively to add perfection to his region of the structure without having the faintest notion of what is being constructed elsewhere, living out his brief life in a social enterprise that extends back into what is for him the deepest antiquity (ants die at the rate of 3-4 per cent per day; in a month or so an entire generation vanishes, while the Hill can go on for sixty years or, given good years, forever), performing the work with infallible, undistracted skill, in the midst of a confusion of others, all tumbling over each other to get the twigs and bits of earth aligned in precisely the right configurations for the warmth and ventilation of the eggs and larvae, but totally incapacitated by isolation, there is only one human activity that is like this, and it is language (6)”.

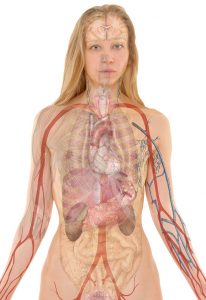

If at this stage you are having any doubts about the reality of the superorganism concept, it would be helpful to remember that you, like all human beings, are a superorganism, in that you are an individual, separate being, composed of various organs, different types of cells etc., all integrated into a functioning, coordinated whole by a central intelligence (the brain).

Here is an example of an ant superorganism at work: “At a state in the construction, twigs of a certain size are needed, and all the members forage obsessively for twigs of just this size. Later, when outer walls are to be finished, thatched, the size must change, and as though given new orders by telephone, all the workers shift the search to the new twigs. If you disturb the arrangement of a part of the Hill, hundreds of ants will set it vibrating, shifting, until it is put right again. Distant sources of food are somehow sensed, and long lines, like tentacles, reach out over the ground, up over walls, behind boulders, to fetch it in (7)”.

So what exactly is a participant in this superorganism, an individual ant? “A solitary ant, afield, cannot be considered to have much of anything on his mind; indeed, with only a few neurons strung together by fibers, he can’t be imagined to have a mind at all, much less a thought. He is more like a ganglion on legs”. However, “It is only when you watch the dense mass of thousands of ants, crowded together around the Hill, blackening the ground, that you begin to see the whole beast, and now you observe it thinking, planning, calculating. It is an intelligence, a kind of live computer, with crawling bits for its wits (8)”. (Thomas thinks that the behaviour of termites is even more extraordinary than that of ants. Bees are also worthy of consideration in the context of superorganisms, as are the highly coordinated, synchronised movements of schools of fish and flocking birds – see bibliography, Sheldrake, p231ff.)

A reasonable conclusion from this would be that each individual ant is being controlled by some external intelligence, and that communication appears to be achieved by non-physical means; the individual ants do not seem to be acting on their own initiative. This idea is stunning enough in relation to insects, but it becomes even more amazing when you consider that the concept is discussed seriously by biologists in relation to Foraminifera, which are relatives of amoeba, and slime moulds.

I’ll take a look first at Foraminifera. An interesting source for this is The Living Stream by Sir Alister Hardy, former Professor of Zoology at Oxford (9). He outlines the problem thus: “…the activities within primitive organisms of certain cells which appear to display elaborate instinctive behaviour patterns and yet are not linked to a nervous system such as would in higher forms be thought necessary for the control of such innate actions”. He goes on to discuss the work of A.W. Kepner on Microstomum, a little free-living freshwater flatworm: (quoting W. H. Thorpe) “Kepner was driven to postulate a group mind amongst the cells of the body to account for the internal behaviour of the Microstomum. Such a conclusion seems to us absurd”. By “us” I assume Thorpe means scientists inclined to materialist explanations. He continues, saying that “behaviour such as this, while striking the ethologist with amazement, is a commonplace of embryology – though the embryologist has no better theory for explaining it than has the ethologist”. Hardy goes on to talk about sponges, which “have no nervous system at all” yet work to a plan – or at least appear to (10) – and protozoa, a relatively simple single-celled animal, before moving on to Foraminifera. He says that some “build houses which are little short of marvels of engineering and constructional skill. I use the word ‘skill’ advisedly… I share the view that the building of these devices cannot be simply a matter of physico-chemical mechanism alone”. “To my mind these various astrorhizid Foraminifera present one of the greatest challenges to the exponents of a purely mechanistic view of life. Here are minute animals, apparently as simple in nature as amoeba, without definite sense-organs such as eyes, and appearing as mere flowing masses of protoplasm, yet endowed with extraordinary powers; not only do they select (his italics) and pick up one type of object from all the jumble of fragments of other sort on the sea-bed, but they build them into a design involving a comparison of size. They build as if to a plan. Here is another mystery worth looking into. There must be an instinct of how to build and some sort of ‘memory’ as to how far they have filled in the spaces and what sizes of spicules remain to be picked up to complete a section. Of course the whole activity of the animal is performed according to the physics and chemistry of the living material; we may be sure that none of these laws are broken… The mystery surely concerns the relation of this ‘psychic’ life of the animal to its mechanical body”.

I’ll turn now to slime moulds. Arthur Koestler, quoting John Bleibtreu, says: “When threatened by famine, the amoeba ‘commence the enactment of an incredible series of activities. These activities are a literal metaphor for the organisation of cells in a multi-celled individual, or the organisation of individuals into a social unit’.

“The amoeba stop behaving as individuals and aggregate into groups, which form clumps…(which) ‘form straggling streamers of living matter, which… orient themselves towards central collection points’ ”. A mound is formed, which eventually topples over, and looks something like a slug which ‘begins now to migrate across the forest floor… It is thought that perhaps some half a million amoeba are involved’.

Koestler then asks the very reasonable questions: “Are the amoeba, so long as they hunt alone, whole individuals – which then become transformed into parts of the slug? … Are bees and termites, whose existence is completely controlled by the interests of the group, possessed of a group mind? (11)”.

Lewis Thomas describes the phenomenon like this: “At first they are single amebocytes swimming around, eating bacteria, aloof from each other, untouching, voting straight Republican. Then, a bell sounds, and acrasin is released by special cells toward which the others converge in stellate ranks, touch, fuse together, and construct the slug, solid as a trout. A splendid stalk is raised, with a fruiting body on top, and out of this comes the next generation of amebocytes, ready to swim across the same moist ground, solitary and ambitious (12)”.

Brian Inglis refers to the Hardy/Foraminifera material, quotes Thomas (as in the previous paragraph), then comments: “The discovery that a chemical rings the bell, the assembly signal for the amoebas to congregate, has tended to be presented as if it were the explanation for the behaviour of the slime mould… How did the amoebas come to congregate in this way? Through chance mutations? The idea is comically far-fetched (13)”.

Also interesting was a piece on the BBC Nature website: Brainless Slime Mould has an External Memory (14). Here are some select quotes, which refer to a study in Australia led by Christopher Reid:

“Slime moulds use a form of spatial ‘memory’ to navigate, despite not having a brain”.

Reid: “The pulsating parts are also influenced by the throbbing of their neighbours within the cell, which means that they can communicate with each other, to pass information through the organism about what is happening in the environment outside”.

“They found that the slime mould did not revisit areas it had already investigated”.

Reid: “In essence, the slime mould is memorising where it has been – storing this memory in the external environment and recalling the information when it later touches the slime-coated area”.

“The findings are the first to identify ‘memory’ in an organism without a brain or central nervous system”.

Reid: “For a single-celled organism, it has continually surprised researchers with its abilities, such as solving mazes, anticipating periodic events, and even making irrational decisions like we do.” “It is truly a remarkable creature that is redefining our notions of ‘intelligence’ ”.

I trust that readers will understand, on the basis of the above information, that the concept of a superorganism or group mind (with its implications of something akin to telepathy) would be difficult for a reductionist, materialist biologist to accept. This is something that will become more apparent as I trace a brief history of how the idea of the superorganism has fared in science.

The term seems to have originated with eminent zoologist William Morton Wheeler, although the idea itself was not original. According to Brian Inglis, “it was implicit in works such as Alfred Espinas’s Des sociétés animales; and made explicit by Charles Riley, Entomologist to the US Department of Agriculture and first President of the Washington Entomological Society, who asserted in 1894: ‘There can be no doubt that many insects possess the power of communicating at a distance of which we can form some conception by what is known as telepathy in man.’ The power, he thought, ‘would seem to depend neither upon scent nor upon hearing in the ordinary understanding of those senses, but rather on certain subtle vibrations (his italics), as difficult to apprehend as is the exact nature of electricity’ (15)”. (For the moment I’ll just note that later science thinks he is wrong about this and return to the subject below.) In similar vein, in a lecture to biologists in 1910, Wheeler said that “biological theories must remain inadequate so long as the study of complex organisms, such as ant colonies, was left to ‘psychologists, sociologists and metaphysicians’, because of ‘our fear of the psychological and the metaphysical’ (16)”. There’s an interesting phrase for you – science is meant to be a search for truth, yet might be afraid of the implications of what it might find!

The story continues about twenty years later when two significant books were published: The Life of the White Ant by Maurice Maeterlinck (17), and even The Soul of the White Ant by Eugène Marais (18) (by ‘white ant’ they mean termite). Both of these books are an incredibly good read. Maeterlinck certainly does not hold back from psychology or metaphysics – he came up with the term ‘spirit of the hive’. Brian Inglis comments: “Because his observations pose embarrassing questions that ethology has been unable to answer without recourse to psi, his work is now rarely mentioned. Yet it is of crucial significance (19)”.

Lewis Thomas observes: “Then, unaccountably, the whole idea abruptly dropped out of fashion and sight. During the past quarter-century (he was writing in 1974) almost no mention of it is made in the proliferation of scientific literature in entomology. It is not talked about. It is not just that the idea has been forgotten; it as though it had become unmentionable, an embarrassment. (Remember Wheeler’s phrase – could this be a fear of the psychological and metaphysical?)

“It is hard to explain. The notion was not shown to be all that mistaken, nor was it in conflict with any other, more acceptable view of things. It was simply that nobody could figure out what to do with such an abstraction. There it sat, occupying important intellectual ground, at just the time when entomology was emerging as an experimental science of considerable power, capable of solving matters of intricate detail, a paradigm of the new reductionism. This huge idea – that individual organisms might be self-transcending in their relation to a dense society – was not approachable by the new techniques, nor did it suggest new experiments or methods. It just sat there, in the way, and was covered over by leaves and papers. It needed heuristic value to survive, and this was lacking (20)”.

Who and what exactly is Thomas talking about? He does not give references, but a good candidate would be The Insect Societies by Edward Wilson (21). Eminent scientist though he is, with an impressive CV (some details below), he nevertheless makes some strange and confusing statements. He opens the book by denying the reality of the superorganism concept, denying any collective activity, and reducing it to a mere analogy: “The insect colony is often called a superorganism because it displays so many social phenomena that are analogous to the physiological properties of organs and tissues. Yet the holistic properties of the superorganism stem in a straightforward behavioral way from the relatively crude repertories of individual colony members, and they can be dissected and understood much more easily than the molecular basis of physiology” (p1).

Later, however, he seems to be suggesting the contrary: “It is all but impossible to conceive how one colony member can oversee more than a minute fraction of the construction work or envision in its entirety the plan of such a finished product. Some of these nests require many worker lifetimes to complete, and each new addition must somehow be brought into a proper relationship with the previous parts. The existence of such nests leads inevitably to the conclusion that the workers interact in a very orderly and predictable manner. But how can the workers communicate so effectively over such long periods of time? Also, who has the blueprint of the nest? (p228)”. He is asking great questions but, as we will see, seems unwilling to contemplate the most obvious (non-materialist) explanations.

The consensus view, to which Wilson subscribes, is that communication is achieved primarily through pheromones, thus via the sense of smell. This is agreed by advocates of the superorganism theory, but it is reasonable to ask whether it really explains anything. Brian Inglis accepts that pheromones “provide the stimuli which prompt termites to action”, something which Eugène Marais had also suspected, and thus provide “a plausible scientific explanation of the way termitaries organise themselves”. Marais, however “had realised… that scent signals could not conceivably account for the complexity of the work undertaken by termite builders, let alone for the termitary’s elaborate architecture”. “Smells or sounds may be the way in which the programme is fed into the computer to get the desired results. They cannot explain how neurons strung together by fibres know how to react, let alone how the instructions are composed. The presumption must be that the forces involved are acting directly on the termites. Something, or somebody, is in effect not merely conducting the orchestra, but also playing all the instruments, and composing the score (22)”. (Remember that Charles Riley, quoted above, thought that the communication did not depend upon scent, and preferred something like telepathy. I suggest again the idea of a group mind.)

Wilson continues to argue against the superorganism concept, but not very convincingly. Relevant statements are:

“The current generation of students of social insects… saw its future in stepwise experimental work on narrowly conceived problems, and it has chosen to ignore the superorganism concept – at least as an explicitly formulated idea” (p318). Why can science not search for the bigger picture, thus the complete truth? Why should it be restricted to “narrowly conceived problems”, subjectively chosen by individual scientists, who may be trying to avoid an issue which they are perhaps unwilling to contemplate?

“The superorganism concept faded not because it was wrong but because it no longer seemed relevant. It is not necessary to invoke the concept in order to commence work on animal societies. The concept offers no techniques, measurements, or even definitions by which the intricate phenomena in genetics, behaviour, and physiology can be unraveled. It is even difficult to cite examples where the conscious use of the idea led to a new discovery in animal sociology” (pp318-319). How is any of this relevant? This merely indicates that he wants to reduce the problem to “genetics, behaviour, and physiology”, i.e. materialist explanations, something he concedes (see below) has proved completely unsuccessful up to his time of writing. How could the concept offer techniques or measurements, since a group mind, if it exists, is not observable in the material world?

He calls the ideas of Maeterlinck (e.g. the “spirit of the hive”) “pretty nonsense” (p318), revealing his bias – this is not the language one would expect from an open-minded scientist.

Having quoted Wheeler, writing in 1928 (23), that biologists at that time were “powerless to offer any solution of the living organism as a whole”, and that the emergent level was “inexplicable”, Wilson comments: “Here, then, is the mirage that drew us on. The words ‘powerless’ and ‘inexplicable’ were a challenge leveled at the next generation. Once the challenge had been taken and progress achieved by technical advancements never conceived of by Wheeler, it was natural for the superorganism concept to become déclassé” (p319). He is thus claiming that later science has gone a long way to explaining the apparent superorganism phenomenon by other ideas, and continues in similar vein: “It might be asked what vision, if any, has replaced the superorganism concept. Surely there is no new holistic conception, as I have tried to make clear in this book” (p319).

So he has reached the conclusion that the concept of the superorganism, in the sense understood by Wheeler, Maeterlinck, and Marais, is incorrect scientifically. However, he then continues with this extraordinary statement: “There exists among experimentalists a shared faith that characterizes the reductionist spirit in biology generally, that in time all the piecemeal analyses will permit the reconstruction of the full system in vitro”. (What a refreshingly honest insight into the minds of biologists! This almost sounds like a religion.) He lists three achievements which would be required in order to achieve this, but then states: “At the present time we cannot come close to any one of these three accomplishments”. He also talks about “the continuing quest for precise evolutionary, that is, genetic, explanations of the origin of sociality and variations among the species in details of social structure, and one has the exciting modern substitute for the superorganism concept” (p319).

So, if biologists have not come close to understanding, and if the quest was continuing, which means that up to that point, as he concedes, it had been unsuccessful, how could he say that the superorganism concept was merely a mirage?

This man is highly intelligent, has been described as the world’s leading authority on ants, has been a Harvard professor, and has won two Pulitzer prizes and many other scientific awards, yet here he reveals himself to be confused as he attempts to defend materialist orthodoxy. As Brian Inglis astutely comments: “Scientists have had little difficulty in evading this issue. This is partly because the habits of termites do not impinge on the everyday life of the community…; partly because of the public’s vague notion that all has been explained by pheromones, or, if not, soon will be by the next advance in biology or biochemistry. It is only recently that suspicions have been aroused that no such advance along conventional lines can provide the answer. The reductionist approach will continue to come up with useful explanations of the pheromone type. It cannot satisfactorily explain the kind of programming necessary to account for termite architecture and design” (pp 28-29). (It’s a shame that Wilson didn’t broaden his interests to include Foraminifera and slime moulds. There is no suggestion of pheromones there, so how would he account for these apparent superorganisms?)

It is therefore perhaps not surprising that famous biologist Rupert Sheldrake, writing in 1988, quotes Wilson (as above regarding the mirage disappearing and the reductionist faith) and concludes: “This approach to animal societies has not so far resulted in a mechanistic understanding of them”. “So here, as in other areas of biology, the question remains wide open. The reductionist faith has been fruitful in stimulating many detailed investigations, but there is no evidence that it will ever provide convincing explanations for the holistic properties of organisms at any level of complexity” (24). (Sheldrake rejects the materialist/reductionist explanation of Wilson, whom he quotes extensively from the book discussed above, and has his own theory of morphic fields. See the bibliography below.)

It is interesting to note that Wilson, with his colleague Bert Hõlldobler, later wrote in 2009 a book called Super-organism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies (25). When I first saw the title, I was pleasantly surprised and wondered if he been converted, or should I say, changed his mind? Having read the book, it would seem not. Although the authors recognise the relevance of the term, and its apparent reality (“we view the insect colony as the equivalent of an organism ”, Pxx), they are still trying to explain it through conventional biology – pheromones, conventional evolutionary theory including natural selection. They claim that reductionism can explain, at least in theory, the emergence of the next level: “When they are well enough known, the parts and processes can be pieced back together and their newly understood properties used to explain the emergent properties of the complex system”. This must be an assumption based on faith, however, since in the same paragraph they concede that biologists “are far from mastering the many complex ways in which species interact to create the higher-level patterns” (Pxix). This echoes the confusion in Wilson’s 1971 book discussed above.

He may be right to reject the superorganism concept, or perhaps it is all just wishful thinking. I note merely that he has been described as a staunch neo-Darwinian; it is just possible this belief has influenced his approach to biology. Perhaps, following the advice of Wheeler, we should not fear psychology and metaphysics.

Bibliography/suggested reading:

Inglis, Brian: The Hidden Power, Jonathan Cape, 1986, pp21-28

Sheldrake, Rupert: Presence of the Past, HarperCollins, 1994, especially chapter 13

Thomas, Lewis: The Lives of a Cell, originally Viking Press 1974. I am using the Penguin 1978 edition.

Footnotes:

(1) see bibliography above

(2) Thomas, p127

(3) Synchronicity, Bantam, 1987, p66

(4) Thomas, p54

(5) Thomas, p54

(6) Thomas, p129

(7) Thomas, p12-13

(8) Thomas, p12

(9) Collins, 1965, pp224 -231

(10) “A multitude of such large cells working together build structures far more complicated than any assembled by a party of workmen putting up a scaffolding against a building”.

(11) Roots of Coincidence, Hutchinson & Co., 1972. I am using the Picador, 1974 edition,

p115-116 (quoting, John Bleibtreu, The Parable of the Beast, 1968, pp215-219),

(12) Thomas, p14

(13) Inglis, p23

(14) www.bbc.co.uk/nature/19846365 by Ella Davies 9/10/2012

(15) Inglis, p24f

(16) Inglis, p25, referring to Wheeler, W.M. “The Ant Colony as an Organism,” Journal of Morphology, 1911, xxii, 307-25

(17) tr. Alfred Sutro, George Allen & Unwin, 1927, 1930

(18) Originally Die Siel van die Mier, J.L. Van Schaik 1933

(19) Inglis, p23

(20) Thomas p127-8

(21) The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971

(22) Inglis, pp25-26

(23) The Social Insects: Their Origin and Evolution, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1928

(24) Presence of the Past, HarperCollins, 1988. Mine is the 1994 edition, p225

(25) W. W. Norton & Co