In the introduction to this series (click here), I considered the possibility that Jesus was a spiritual master, thus a human who had achieved the goal of the spiritual path, to reunite with the divine essence, thus a man who had become a god. This idea is usually associated with Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sufism, thus spiritual religions. Here I am going to consider the same idea from the perspective of an esoteric school. This, so it seems to me, is the theme of Shakespeare’s last play The Tempest, which is profoundly heretical from a Christian point of view. In the opening scene, on a boat during a violent storm, the boatswain asks Gonzalo, described as ‘an honest old counsellor’, to still it in these words: “If you can command these elements to silence, and work the peace of the present, we will not hand a rope more. Use your authority…”. This is a very strange request; why on earth would he think that the human Gonzalo might have the power to do that? (In fact he doesn’t, even though he is later described as “Holy Gonzalo, honourable man”.) The one well-known person in ‘history’ reputed to have done that is Jesus; Matthew’s gospel (8.23-27) says that during a storm “he got up and rebuked the winds and the sea; and there was a dead calm. They were amazed, saying, ‘What sort of man is this, that even the words and the sea obey him?’ ”. (See also Mark 4.35-41, and Luke 8.22-25.) This passage, in my opinion, is the inspiration for, and therefore casts a long shadow over the whole of The Tempest. Christians might think that Jesus’s miracles are evidence of his divinity. His own disciples make this mistake; having seen him walk on water, they conclude: “Truly you are the Son of God” (Matthew 14.33). This contradicts, however, what Jesus himself said, that any of his disciples could do the things he does, if they only have faith (Matthew 17.20), suggesting that such powers are possible for all humans.

In the introduction to this series (click here), I considered the possibility that Jesus was a spiritual master, thus a human who had achieved the goal of the spiritual path, to reunite with the divine essence, thus a man who had become a god. This idea is usually associated with Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sufism, thus spiritual religions. Here I am going to consider the same idea from the perspective of an esoteric school. This, so it seems to me, is the theme of Shakespeare’s last play The Tempest, which is profoundly heretical from a Christian point of view. In the opening scene, on a boat during a violent storm, the boatswain asks Gonzalo, described as ‘an honest old counsellor’, to still it in these words: “If you can command these elements to silence, and work the peace of the present, we will not hand a rope more. Use your authority…”. This is a very strange request; why on earth would he think that the human Gonzalo might have the power to do that? (In fact he doesn’t, even though he is later described as “Holy Gonzalo, honourable man”.) The one well-known person in ‘history’ reputed to have done that is Jesus; Matthew’s gospel (8.23-27) says that during a storm “he got up and rebuked the winds and the sea; and there was a dead calm. They were amazed, saying, ‘What sort of man is this, that even the words and the sea obey him?’ ”. (See also Mark 4.35-41, and Luke 8.22-25.) This passage, in my opinion, is the inspiration for, and therefore casts a long shadow over the whole of The Tempest. Christians might think that Jesus’s miracles are evidence of his divinity. His own disciples make this mistake; having seen him walk on water, they conclude: “Truly you are the Son of God” (Matthew 14.33). This contradicts, however, what Jesus himself said, that any of his disciples could do the things he does, if they only have faith (Matthew 17.20), suggesting that such powers are possible for all humans.

The whole play can be seen as a portrayal of the process of what it takes for a human to become godlike, and therefore perform miracles. In the second scene, immediately after the one above, we are informed that you do not have to be divine to have control over the weather, rather a human magician, Prospero, has the power to create a storm, and therefore to stop it. At least that is what his daughter Miranda suspects; she implores him: “If by your art, my dearest father, you have put the wild waters in this roar, allay them”. Prospero agrees that he has created the storm, and further, that he has taken care to make sure that no one on the boat was harmed. (It is later revealed that he has achieved this because he has magical power over the spirit Ariel: “Hast thou, spirit, performed to point the tempest that I bade thee?” Ariel replies: “To every article”.)

The whole play can be seen as a portrayal of the process of what it takes for a human to become godlike, and therefore perform miracles. In the second scene, immediately after the one above, we are informed that you do not have to be divine to have control over the weather, rather a human magician, Prospero, has the power to create a storm, and therefore to stop it. At least that is what his daughter Miranda suspects; she implores him: “If by your art, my dearest father, you have put the wild waters in this roar, allay them”. Prospero agrees that he has created the storm, and further, that he has taken care to make sure that no one on the boat was harmed. (It is later revealed that he has achieved this because he has magical power over the spirit Ariel: “Hast thou, spirit, performed to point the tempest that I bade thee?” Ariel replies: “To every article”.)

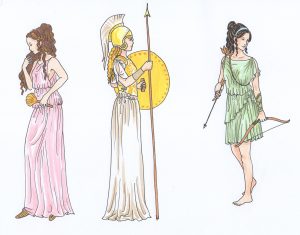

In the language of symbolism, the sea represents the fluid psyche, and islands represent consciousness in the material world, the dry land which has emerged from the unconscious. The theme of the play, which takes place on this island, is therefore the evolution of consciousness, what it takes for a human to become godlike, and therefore acquire the same powers that Jesus has (1). The aspirant challenged with this task is Ferdinand, son of the King of Naples, who has arrived on the island following the shipwreck. His qualification for this role is immediately apparent when Miranda (who represents the divine feminine), upon seeing him for the first time says: “I might call him a thing divine; for nothing natural I ever saw so noble”. This is truly love at first sight! She had suspected, somewhat prophetically, that someone like this might arrive; she earlier had described the ship she wanted Prospero to save as “a brave vessel who had no doubt some noble creature in her”. The feeling is mutual; Ferdinand says: “O, if a virgin, and your affections not gone forth, I’ll make you the Queen of Naples”. It is not hard to predict the eventual outcome; they will indeed be married. Prospero, however, cannot allow this to happen too suddenly (“They are both in either’s powers: but this swift business I must uneasy make, lest too light winning make the prize light”), and Ferdinand has to transform his human nature, in order to prove himself worthy of Miranda. He therefore has to submit himself to the authority of Prospero (“I charge thee that thou attend me”), who calls him a spy, a traitor, an impostor, presumably to test his sincerity, and threatens him with some unpleasant experiences: “I’ll manacle thy neck and feet together. Sea-water shalt thou drink; thy food shall be the fresh-brook mussels, wither’d roots, and husks wherein the acorn cradles”. Ferdinand is unwilling and attempts to draw his sword, symbolising his inner resistance to what he has to undergo, but Prospero’s magic prevents him. Ferdinand then yields, and submits himself to the will of Prospero, who much later reveals: “All thy vexations were but my trials of thy love, and thou hast strangely stood the test”. I have never undergone such experiences myself, and am not involved with any such group, but all this sounds like the path that an aspirant has to follow in an esoteric secret society, the initiatory tests and tasks he has to go through in order to achieve his divinity, and thus be worthy of uniting with Miranda, the divine feminine (Ferdinand describes her: “You, so perfect and so peerless, are created of every creature’s best”). As an example, at the beginning of Act 3 we see Ferdinand engaged in an extremely arduous task that he has been charged with: “I must remove some thousands of these logs, and pile them up, upon a sore injunction”. He understands, however, that this is what he has to do in order to win Miranda: “This my mean task would be as heavy to me as odious, but the mistress which I serve quickens what’s dead, and makes my labours pleasures”. (Note that here and later in the speech he uses the word labours, the same word used in connection with Hercules, who is also a spiritual aspirant in the process of becoming a god.) Later they pledge themselves to each other (Act 3, scene 1, 83-90), Miranda already having broken a promise to Prospero that she will not reveal her name. So we see that the process is moving on towards its inevitable conclusion – their strong attraction will overcome all obstacles. In Act 4, scene 1, Prospero concedes that Ferdinand’s trials may have been excessive (“If I have too austerely punish’d you”), but, as noted above, “All thy vexations were but my trials of thy love, and thou hast strangely stood the test”. He now offers Miranda’s hand in marriage, and an elaborate ceremony takes place. Evidence that this marriage has divine significance is that three goddesses – Iris, Ceres, and Juno, queen of the Gods – attend (2).

While all this is going on, we enter into the worlds of the other two groups on the island. There is Caliban, son of the witch Sycorax, an obviously ugly, sub-human creature (3). In the past he has attempted to rape Miranda, and is now Prospero’s slave. All in all, he is a rather unsavoury character, a ‘man’ in the grip of his base instincts.

He is unredeemed, a lost soul. It is tempting to make a connection with the Fall of Christian theology. His name is almost an anagram of Cain and Abel, an amalgamation of the two words; they were, of course, the eldest sons of Adam (thus the first fruits of Original Sin), and Cain was the world’s first murderer. Caliban, as we will discover, has most certainly eaten of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

He is unredeemed, a lost soul. It is tempting to make a connection with the Fall of Christian theology. His name is almost an anagram of Cain and Abel, an amalgamation of the two words; they were, of course, the eldest sons of Adam (thus the first fruits of Original Sin), and Cain was the world’s first murderer. Caliban, as we will discover, has most certainly eaten of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

He calls Prospero a tyrant, and curses him by wishing infections and disease upon him; he thus does not recognise that, as his true master, he is the source of his potential redemption. Instead he makes an alliance with Stephano, a new arrival on the island following the storm; he is intoxicated by the wine provided by him, an obvious allegory of confusion, lack of conscious awareness.

He calls Prospero a tyrant, and curses him by wishing infections and disease upon him; he thus does not recognise that, as his true master, he is the source of his potential redemption. Instead he makes an alliance with Stephano, a new arrival on the island following the storm; he is intoxicated by the wine provided by him, an obvious allegory of confusion, lack of conscious awareness.

Further evidence of the connection with Original Sin is that Caliban asks Stephano if he is a fallen angel (“hast thou not dropp’d from heaven?”). The best known fallen angel who has rebelled against God, in Christian theology, is Satan (4). (Caliban also describes Stephano as “a brave god”.) He is choosing therefore to ally himself with someone he perceives to be an opponent of God (“I prithee be my god”), who he thinks will be able to free him from Prospero. (Stephano asks him to swear his allegiance on “the book”, presumably an indirect reference to the Bible, but the book he uses is actually the bottle of liquor. Taking this oath will therefore render Caliban more intoxicated, that is, increase his confusion.) He refuses to submit to the tasks demanded by Prospero, but willingly agrees to perform similar ones for his new master (“I’ll pluck thee berries; I’ll fish for thee, and get thee wood enough”).

At this point, Stephano’s companion Trinculo represents the voice of what Caliban should be thinking, thus perhaps his conscience. (He calls him “a very shallow monster”, “a very weak monster”, “a most poor credulous monster”, “a most perfidious and drunken monster”, and suspects that he will not be faithful to Stephano’s instructions: “When ‘s god’s asleep he’ll rob his bottle”. Trinculo also knows the true nature of Stephano; he calls Caliban “a most ridiculous monster, to make a wonder of a poor drunkard”.)

Caliban believes that he (fallen man) is the true ruler of the island (consciousness, the material world), but that the tyrant and sorceror Prospero (the ruler of the island – God?) has cheated him out of it. He therefore wants Stephano to kill Prospero, replace him as lord, and Caliban will then serve him. He offers Miranda to him (offers the divine feminine to a fallen angel). Stephano promises to kill Prospero, and that he and Miranda will become King and Queen. At this point even the previously clear-thinking Trinculo has succumbed, and agrees that this is an excellent plot.

A brief aside

There is a parallel process in the lives of Caliban and Ferdinand. Both are under the control of Prospero, who sets them tasks. Interestingly, they are both charged with carrying wood. Prospero says of Caliban, “he does make our fire, fetch in our wood”. As if to insist on the point, during Act 2, scene 2, Shakespeare has Caliban entering “with a burden of wood”. In Act 3, scene 1, Ferdinand enters “bearing a log”. This cannot be mere coincidence. If something is repeated several times, it must be important – there must be some symbolic significance about carrying wood. A simple interpretation would be very hard work, also a menial task, something calculated to eliminate the ego of the spiritual aspirant, any notion of being special. (There may be deeper meanings to those who understand such matters.) Ferdinand accepts the challenge, but Caliban rebels, has ideas above his station. He allies himself with Stephano and, as noted above, will pick berries, fish and find wood for his new, false master.

The other group (principal members Alonso, Sebastian, Antonio) may be of more noble birth than Caliban, but their behaviour is little better. When they arrive on the island, they should have a guilty conscience from their past misdeeds. Specifically, Ariel singles out these three, those who are most responsible for Prospero’s exile, as “three men of sin”. They are guilty of removing Prospero as Duke of Milan, abusing his trust, and exiling him and Miranda. They are thus motivated by power and money, their lower, instinctual nature.

Shakespeare insists, however, that on this island they have arrived with fresh clothes, thus indicating the possibility of a fresh start, or as the expression goes, turning over a new leaf. This is repeated several times. In Act 2, scene 1, Gonzalo says that it is “indeed almost beyond credit that our garments, being, as they were, drench’d in the sea, hold, notwithstanding, their freshness and glosses, being rather new-dy’d, than stain’d with salt water”. In case we missed it the first time, a few lines later he says “Methinks our garments are now as fresh as when we put them on first in Afric”. Then again a few lines later: “Sir, we were talking that our garments seem now as fresh as when we were at Tunis…”, and again, “Is not, sir, my doublet as fresh as the first day I wore it?”

Gonzalo is a decent man, not involved in all the previous plotting. He may therefore represent the voice of their conscience, trying to draw their attention to this fresh start, this new opportunity for redemption. Are they willing to listen? It would seem not; Antonio and Sebastian clearly have not repented of their past actions, for they begin to repeat them during the play by plotting to kill Alonso and the honourable Gonzalo. They are on the point of doing so when interrupted by Ariel.

There remains only the need to consider the figure of Prospero, who is somewhat ambiguous. He is a human magician, and also, as a human, he is a deposed ruler, rebelled against by the base instincts of other humans. Sometimes, however, he seems rather to be a divine figure. He is, after all, the father of the divine feminine (Miranda), and in control of, thus the ruler of, the island, one could therefore argue God. In the allegory, God the King is deposed by Satan – humans succumb to their lower, base nature, that is to say, murder, rebellion, sexual violence, drunkenness.

He also sometimes adopts roles usually associated with Jesus: the judge of souls, and in the final scene, the forgiver of sins. He duly forgives all those who have wronged him, even though their sins have been appalling. At the very least, he is putting Jesus’s instructions into practice, that we should always forgive our enemies unconditionally. To continue with resentment is said to be a burden.

He sets Ariel free, as promised. Also, he even sets free Caliban, who is beginning to show signs of self-awareness. He is embarrassed by his earlier mistakes, saying that, “I’ll be wise hereafter, and seek for grace. What a thrice-double ass was I, to take this drunkard for a god, and worship this dull fool!”

Miranda celebrates the transformation of everyone’s consciousness, and looks forward to a brighter future: “O, wonder! How many goodly creatures are there here! How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world that has such people in’t!”

Conclusion

The Tempest clearly shows that Shakespeare was reacting strongly against the idea that one needs to be divine in order to perform ‘miracles’. It is not clear, however, whether Shakespeare thought that Jesus was actually an esoteric magician. The gospels, however, certainly portray him as having such powers. Is it possible therefore that Jesus was himself a magician involved with some secret group? Scholars are uncertain as to what milieu Jesus emerged from, what his ideological origins were (although various claims are made). This would therefore remain an open question.

As stated in the article, I have no inside knowledge of secret societies, or of magic and esotericism, so all the above is based purely upon my own observations, and what I have learned from my reading. I am aware of the existence of, but have not read, The Timeless Theme by Colin Still, and Majesty and Magic in Shakespeare’s Last Plays, by Francis Yates. I would therefore recommend them to anyone wishing to explore this subject more deeply.

It seems beyond doubt that, in order to write The Tempest, Shakespeare must have been associated with some such esoteric group, since the play is an obvious advertisement for it. Which secret society? I have no way of knowing for sure, but I understand that Frances Yates in her book describes the play as a Rosicrucian manifesto.

Footnotes:

(1) Even though the play takes place on solid land (an island, the material world), it is implied that standing behind that is the mysterious world of the psyche. At one point Gonzalo asks his companions to rest, because he is exhausted from walking the maze that is the island. The word is repeated in the final scene, when Alonso says: “This is as strange a maze as e’er men trod”. A maze or labyrinth is an obvious symbol of the irrational, internal world of the psyche (compare the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur). Alonso continues: “There is in this business more than nature was ever conduct of”, thus this island is beyond rational comprehension.

(2) This sacred marriage is also known as the hieros gamos. Carl Jung calls it the Mysterium Coniunctionis. His book of that name has the subtitle An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy. That seems a good description of what is happening between Ferdinand and Miranda.

(3) The Dramatis Personae describe him as “savage and deformed”, and he is described by Stephano and Trinculo as a “moon-calf”, a “monster” – and they are his friends!

(4) although Stephano replies, presumably as a joke to taunt Caliban, that he is the Man in the Moon.