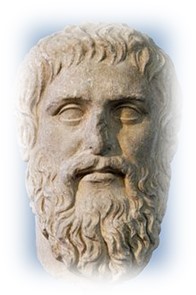

THE ONGOING INFLUENCE OF PLATO

Plato was perhaps the most significant of the ancient Greek philosophers. In The Republic (part seven, book seven) he offers us possibly the most enduring piece of philosophy ever written, his allegory of the cave. It’s worth checking out the original, but here is a brief summary of the essential idea.

Plato compares the human condition to prisoners in a cave, chained so that they can only look straight ahead of them and cannot turn their heads. All they can see is a wall onto which are projected shadows of figures who are in reality standing behind them. Since that is all they have known, they take these shadows to be reality, and do not understand that what they are seeing is something emanating from elsewhere, a by-product of a different level of reality.

Two obvious points can be made about this. Since shadows are non-material, this is a decisive statement in favour of the philosophy of Idealism – what appears to be matter is an illusion; there is nothing but consciousness. Secondly, this is exactly what Eastern religions have been saying for thousands of years; the word they use is maya (1).

So how important is Plato and his thinking? Is this allegory just some silly story from ancient time that we can comfortably dismiss? Well, the important twentieth century philosopher Albert North Whitehead said that “the European philosophical tradition…. consists of a series of footnotes to Plato” (2). He was perhaps biased as he had Platonic leanings himself, but his comment does stand up to scrutiny. Others who have expressed themselves in similar language are:

Helena Blavatsky, the co-founder of the Theosophical Society, who said: “Although twenty-two and a quarter centuries have elapsed since the death of Plato, the great minds of the world are still occupied with his writings. He was, in the fullest sense of the word, the world’s interpreter” (3).

Ralph Waldo Emerson, a giant from the world of American spirituality, who said: “Out of Plato come all things that are still written and debated among men of thought. … Plato is philosophy, and philosophy, Plato… …and the thinkers of all civilized nations are his posterity, and are tinged with his mind” (4).

Turning now to the allegory of the cave, here are a few significant landmarks from history, beginning with what I perceive to be the most important, the quantum revolution in physics. For centuries there had been speculation about the nature of the ultimate building blocks of matter. In the early twentieth century the necessary technology was developed to investigate the question more fully. As soon as the world’s leading scientists were able to understand what was really going on at the subatomic level, the early quantum physicists took a decidedly Platonic (idealist) turn. The most eye-catching quote, which encapsulates the whole idea perfectly, comes from Sir James Jeans: “The universe is looking less like a great machine, and more like a great thought”. He actually uses Plato’s allegory of the cave as the epigram for his book! (5)

Equally significant are the thoughts of Sir Arthur Eddington who, clearly thinking of Plato, said: “Matter and all else that is in the physical world have been reduced to a shadowy symbolism”. The material world “which seems so vividly real to us is probed deeply by every device of physical science and at bottom we reach symbols. Its substance has melted into shadow” (both my italics) (6). Werner Heisenberg also made the same point: “Modern physics has definitely decided for Plato. For the smallest units of matter are not physical objects in the ordinary sense of the word: they are forms, structures, or – in Plato’s sense – ideas” (7).

So an interesting question for modern scientists is, how did Plato manage to be over two thousand years ahead of his time? He understood something essential about the nature of reality, presumably without the technology available to twentieth century scientists.

Unsurprisingly, Plato remains a strong influence in spiritual traditions. In Theosophy I have already made reference to Helena Blavatsky (see footnote 1). Annie Besant, another leader of the Theosophical Society, also uses the language of Plato:

“A history only gives a story of the shadows, whereas a myth gives a story of the substances that cast the shadows”.

“These multifarious workers in the invisible worlds cast their shadows on physical matter, and these shadows are “things” – the bodies, the objects, that make up the physical universe. These shadows give but a poor idea of the object that casts them”.

“History is an account, very imperfect and often distorted, of the dance of these shadows in the shadow-world of physical matter” (8).

St. Paul, while using a different image, here seems to be alluding to the same idea: “For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then (i.e. when the illusion is removed) we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully” (p9). This passage has also been translated: “At present all we see is the baffling reflection of reality; we are like men looking at a landscape in a small mirror. The time will come when we will see reality whole and face to face” (10). This makes the connection with the cave allegory more clearly.

Islam is also comfortable with the idea. The Sufi writer Abu Bakr Siraj ad-Din (Martin Lings) said: “…if a world did not cast down shadows from above, the worlds below it would vanish altogether, since each world in creation is no more than a tissue of shadow entirely dependent on the archetypes in the world above” (11)..

Other significant moments from history are:

Philo Judaeus. We know that the Jewish religion can be very isolationist at times. This highly significant Jewish philosopher nevertheless felt the need to accommodate Jewish thinking with Plato. In the words of David T. Runia: “Philo tried to show that Jews need not be ashamed of their heritage, that loyalty to the Law did nod entail a rejection, but precisely a deepening of the ideas of Hellenism” (12).

The continuation of Plato’s ideas by Plotinus, Proclus, Porphyry and others from the third century onwards, which we now call Neo-Platonism, although these figures would have called themselves merely Platonists.

The spectacular Italian Renaissance was a rebirth of ancient traditions, especially Greek ones including Plato.

One of England’s greatest poets William Blake seemed to live in touch with higher levels. The Blake expert Kathleen Raine describes him as a Platonist (13). In these lines from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell Blake seems to be referring directly to Plato’s allegory: “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all thing thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern”.

I have always thought of the artist René Magritte as being influenced by Plato. He is very keen on the idea of an artist’s painting being indistinguishable from the real image it depicts, an idea which obviously has some relationship to the allegory of the cave. I was fortunate to attend an exhibition recently at the Schirn Gallery in Frankfurt, where I saw his painting La Condition Humaine (The Human Condition), which is one of several works by him on this theme. I had obviously seen it before, but suddenly noticed that it looks out from a cave, inside of which is a fire. This immediately reminded me of Plato’s allegory. It was therefore a pleasant surprise when within two minutes I saw a text on the wall describing the influence of Plato’s allegory on Magritte:

“(Some philosophers regard visual representations) as products of perceptions that are removed from reality and ultimately amount to nothing more than the play of shadows. We have learned to accept them as real through conventions and customs that hold us captive. Magritte depicted Plato’s allegory expressly in many works by isolating and reassembling its essential elements – the fire and the view from an enclosed space such as a cave, a room, or a house”.

The film-maker David Lynch seems to be heavily influenced by Plato. Of course, all cinema is a brilliant metaphor for Plato’s cave allegory, since the audience is watching images projected onto a screen, images which do not really exist, but have been created previously elsewhere. The audience can become engrossed in the film, and begin to take it for a real story. Lynch takes this idea and pushes it to its limits in his masterpiece Mulholland Drive, which is an attempt to awaken the audience to the reality of a multi-levelled universe via Plato’s allegory. The opening scene shows a soul emerging against a background of shadows on a wall! (14)

The psychologist and neurologist John R. Smythies called his book on the nature of consciousness The Walls of Plato’s Cave (15). The novelist and writer Graham Dunstan Martin calls his very interesting book on the nature of consciousness Shadows in the Cave, and unsurprisingly begins with an account of Plato’s allegory (16).

So Plato’s allegory has been an inspiration for spiritual seekers, scientists, poets, artists, and film-makers. Does this have any relevance for modern times? I believe that it does, especially for science and politics. I’ll return to that topic in a later post.

Footnotes:

1. As Helena Blavatsky says: “Life is thus a dream, rather than a reality. Like the captives in the subterranean cave, described in The Republic, the back is turned to the light, we perceive only the shadows of objects, and think them the actual realities. Is not this the idea of Maya, or the illusion of the senses in physical life, which is so marked a featre in Buddhistical philosophy?” (Isis Unveiled, volume 1, preface Pxiii)

2. Process and Reality, Free Press, 1979, p39

3. Isis Unveiled volume 1, preface Pxi

4. Complete Prose Works, Ward, Lock & Co, 1900, p169. Emerson’s essay on Plato gives some insight as to why he is held in such high regard.

5. The Mysterious Universe, Cambridge University Press, 1930, this edition 1947

6. Science and the Unseen World, 1929, this edition Quaker Books 2007, pp21, 23

7. Ken Wilber, Quantum Questions, Shambala, 1984, p51. Quoted by Rupert Sheldrake, The Science Delusion, Coronet, 2012, p88

8. Esoteric Christianity, Chapter 5 The Mythic Christ

9. 1. Corinthians 13.12, NRSV translation

10. by J. B. Phillips, quoted in Mysticism: A Study and an Anthology, F. C. Happold, Penguin, 1970, p194

11. The Book of Certainty: The Sufi Doctrine of Faith, Vision and Gnosis, Samuel Weiser, 1974. Quoted by Kenneth Oldmeadow, Traditionalism: Religion in the Light of the Perennial Philosophy, The Sri Lanka Institute of Traditional Studies, 2000, p104

12. Philo of Alexandria and the Timaeus of Plato, E. J. Brill, Netherlands, 1986, p37

13. William Blake, Thames and Hudson, 1970, p49, p113

14. David Lynch is known to be a long-term Transcendental Meditation practitioner. He talks in terms one would expect of stilling the mind and discovering bliss. His inner journey, however, seems to have given him extraordinary insight into the nature of the psyche, as Mulholland Drive demonstrates. Though the film is deemed cryptic and hard to understand, it was nevertheless voted best film of the millennium in a poll of 177 film critics in 2016.

15. 1994, Ashgate Publishing

16. Arkana, 1990