This article follows on from The Psychology of Atheism, and makes best sense if readers are familiar with it.

In Faith of the Fatherless (1) Paul Vitz developed his Defective Father Hypothesis. He explains that those he calls ‘intense atheists’, especially those who are hostile to Christianity, which focuses upon the idea of God as a loving father, have all suffered disappointment in and resentment of their own fathers which “unconsciously justifies (their) rejection of God”. It is especially significant when a father dies while the child is alive, which is worst when it happens between the ages of three to five. In simple terms, traumatic events in early childhood, especially those in relation to the father, are likely to lead to extreme atheism.

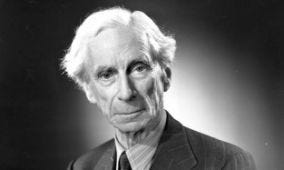

In my previous post in this series I discussed Sigmund Freud in the light of the above. I’m now going to highlight, in the context of Vitz’s hypothesis, some of the philosophers and scientists who have appeared in my recent articles, beginning with the philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell. He was one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century, and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. A significant title is Why I am not a Christian. An intense atheist philosopher friend of mine describes him as one of his greatest influences.

In my article The ‘Enlightenment’ — Where It Has Taken Us, I quoted Russell describing his understanding of humanity and the universe: “That man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling can preserve an individual life beyond the grave … (continues) All these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand. Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built” (2).

Here is what Vitz has to say about Russell (3). His father died when he was four years old. “Young Bertrand was present at the end… To make matters worse, Russell’s mother had died two years earlier. Bertrand was subsequently cared for by his grandparents… but his grandfather… died in 1878 when Bertrand was six”. His grandmother was known as the “Deadly Nightshade”. She was his “greatest childhood influence, was by birth a Scottish Presbyterian, by temperament a puritan. The atmosphere of her religion was ‘a mournful Christian humility’ ”. “Russell’s only other parent figures were a string of nannies to whom he often grew very attached: when one of his beloved nannies left, eleven-year-old Bertrand was ‘inconsolable’ ”.

Russell “very early became an agnostic or atheist”. Vitz says that “for men, God seems to function primarily as a principle of justice and order in the world… we would expect… that men who become atheists will find a new absolute principle with which to order the world. Thus, we expect male atheists to be quite explicitly atheistic and to have a new ‘divinity’ that takes the intellectual place of God. As a consequence, atheistic men should be intense believers in such alternative principles as reason, science, progress, humanism, socialism, communism, or existentialism”.

It seems therefore that human beings have a need, or at least a strong tendency, to worship; if they reject God, a substitute will be found. Russell’s daughter Katherine is quoted: “I believe myself that his whole life was a search for God, or, for those who prefer less personal terms, for absolute certainty”. Vitz says that she “was quite aware of his search for certainty in mathematics as a religiously motivated substitute for God”. Russell himself is quoted: “I wanted certainty in the kind of way in which people want religious faith”, and Vitz says that “the early deaths of his parents and grandfather, plus his frequent ‘lost’ nannies, could easily be the source of his incredible desire for certainty”.

The events of his early life clearly left him traumatised and, it would seem, profoundly affected his adult character: “Bertrand Russell’s arrogance, intense hatreds, psychopathic coldness, and his frequent lies are discussed in a major recent biography by Ray Monk” (4). He avoided human warmth and relationships, saying: “I am conscious that human affection is to me at bottom an attempt to escape from the vain search for God”. Instead, he soon discovered that “one way out of the sadness of these constantly changing companions was reading, retreating into a distant and increasingly abstract world”.

We can see from the above that religious questions, despite his professed atheism, completely dominated his life (5). One can only feel sympathy for Russell, given the extremely distressing circumstances and events of his early childhood. I am still left wondering how a severely depressed, gloomy individual desperately in need of therapy became one of the most influential figures of the twentieth century. I assume he was an impressive mathematician, but his philosophy, which was built on a “firm foundation of unyielding despair”, emerged from the depressing events of his own life, and should not have been projected onto humanity. The sentiments he expressed from within his neurosis have nevertheless been accepted by materialist science, and have become the dominant philosophy of our times. Such, it would seem, is the strong appeal of atheism.

Footnotes:

(1) Spence Publishing Company, 1999

(2) The Free Man’s Worship, 1903, https://users.drew.edu/jlenz/br-free-mans-worship.html

(3) for what follows see pp26–28 and p110

(4) Vitz, p142. He is referring to Bertrand Russell: The Spirit of Solitude, 1872–1921, Free Press, 1996

(5) This was also the case with Freud, the subject of my previous article. Vitz had previously devoted a whole book to that topic, Sigmund Freud’s Christian Unconscious, in which he explores his fascination with Roman Catholicism. (William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1988)