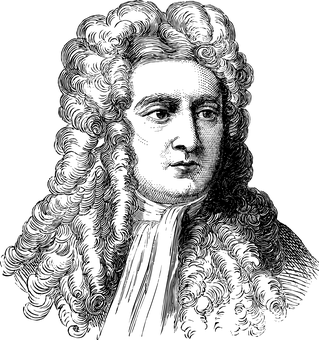

This article is the second in a series about alchemy. In the first I discussed the career of Sir Isaac Newton, and how his passion for alchemy and its related philosophy influenced and led to his scientific ideas. Here I’m going to try to address the question of how alchemy might be achieved. For the record and to avoid any misunderstanding, I should perhaps say that I am not an alchemist, have never tried it, have no inside knowledge about it, nor am I a member of any secret society. What follows therefore are personal reflections, pure speculation from an outsider’s perspective about how alchemy might be successful.

According to the modern scientific worldview, the transmutation of one element into another is obviously considered impossible, ridiculous even to contemplate, and belief in it even a sign of madness (e.g. Grant Piper’s article, the inspiration for this series). In order to hypothesise how it might be possible, we therefore have to find an alternative understanding of how the universe works. In very general terms, the scientific worldview is based on the premise that matter precedes mind. All the great religions and esoteric traditions, however, say that mind precedes matter, that the primal state of the universe is a oneness of pure consciousness (i.e. the divine mind), and that everything that exists, whether material or otherwise, has ultimately been thought into existence by this primal Oneness.

In his book The Secret History of the World¹ Jonathan Black describes in detail the worldview of esoteric secret societies, and his account of this process is as good a starting point as any². He says that at the beginning there was noTHING, that “something must have happened before there was anything” to bring things into existence, and that “this first happening must have been quite different from the sorts of events we regularly account for in terms of the laws of physics”. He suggests that this first happening was a mental event, an impulse from the divine mind. The process continues in this way: “The birth of the universe, the mysterious transition from no-matter to matter has been explained” as “a series of thoughts emanating from the cosmic mind. Pure mind to begin with, these thought-emanations later became a sort of proto-matter, energy that became increasingly dense, then became matter so ethereal that it was finer than gas, without particles of any kind. Eventually the emanations became gas, then liquid and finally…”, “at the lowest level of the hierarchy… these emanations… interweave so tightly that they create the appearance of solid matter”. Therefore, these “emanations from the cosmic mind should be understood… as working downwards in a hierarchy from the higher and more powerful and pervasive principles to the narrower and more particular, each level creating and directing the one below it”.

I would suggest that this account is consistent with Hinduism, ancient Egyptian religion, Gnosticism, Taoism, Kabbalism (esoteric Judaism), the spiritual tradition of ancient Greece (for example Thales, Pythagoras, Plato), and therefore neo-Platonism (Plotinus etc.). In modern times Theosophy, Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy, and other esoteric schools, for example Rosicrucianism, would also concur.

In case any Christians reading this are thinking that all this has nothing to do with them, I should point out that this process is also described in Genesis chapter 1. There the cosmic mind of God creates light, the fundamental energy which is the basic building block of the universe, and then proceeds to create from it other levels — heavens, higher and lower waters, and eventually dry land (the material universe).

Even mainstream science has a similar understanding, even though it is a kind of limited caricature of the spiritual worldview. In the beginning there was nothing, an infinitely small and dense singularity which, for unknown reasons, exploded into existence, producing a chaos of subatomic particles, which eventually became the physical universe we know through a process of increasing densification.

In both the scientific and spiritual worldviews, something akin to alchemy must have gone on at some point, in that one form of existence was transmuted into others; neither side disputes that elements were formed from a more primal level. In the context of alchemy, since lead and gold obviously did not exist at the beginning of the universe, even conventional scientists must concede that they came into existence. They will presumably say that this occurred ‘naturally’, and that blind forces were responsible. The spiritual viewpoint says that it was rather the operation of supernatural intelligence.

As a non-scientist, my best understanding of what makes one chemical element different from another is the number and arrangement of electrons around the nucleus of each atom. At some prior level of existence therefore, there were electrons existing purely as electrons (along with other particles), not yet transformed into the different elements. There is therefore no reason, at least in theory, why even a conventional scientist could not somehow figure out how this happened, and then reproduce the process. This seems highly unlikely of course, so we have to turn to spiritual alchemy for more insight into how this might be achieved.

Is alchemy literally possible, purely through physical, quasi-scientific procedures? I’ll leave that an open question for the time being, but assume for the sake of argument that the answer is no. As we have seen, the spiritual, esoteric worldview says that the whole universe is understood in terms of mental events generating physical events. Could that be the explanation for how alchemy might be achieved? Here are some thoughts on the estoteric worldview from Jonathan Black (relevant to, but not referring specifically to alchemy).

- “Matter is therefore moved by human minds perhaps not to the same extent, but in the same kind of way that it is moved by the mind of God” (p34).

- “Our emotional states directly affect matter outside our bodies. In this psychosomatic universe the behaviour of physical objects in space is directly affected by mental states without our having to do anything about it. We can move matter by the way we look at it” (p 35).

- “The belief that the deepest springs of our mental life are also the deepest springs of the physical world, because in the universe of the secret societies all chemistry is psycho-chemistry, and the ways in which the physical content of the universe responds to the human psyche are described by deeper and more powerful laws than the laws of material science” (p 36).

This all sounds somewhat cryptic, but provides some clues. For alchemy to be successful along these lines, we would have to assume that a human being has hidden, paranormal powers, specifically psychokinesis, the ability of mind consciously to affect matter. This is a controversial topic in parapsychological research, some saying that it is a real ability, while others are unconvinced.

In Hinduism, as one progresses on the spiritual path, as consciousness rises through the various levels through spiritual practice, it is said that one may acquire siddhis, “material, paranormal, supernatural, or otherwise magical powers, abilities, and attainments”³. The advice given is that no attention should be paid to them, since they are a distraction from the true purpose, which is to reunite with one’s divine essence, a state of pure consciousness. These powers are nevertheless recognised as real.

Based on everything I’ve said so far, at some point on the spiritual path, as one rises gradually towards a reunion with one’s divine essence, logic suggests that one must reach a point of development analogous to the mind of a creative deity, a level from which one can transmute substances by the power of thought.

How does this relate to practising alchemists? Do we find them merely indulging in weird, purely physical experiments, or are they engaged in spiritual practices? Michael White, my primary source in the preceding article⁴, quotes Isaac Newton: “Those who search after the Philosophers’ Stone [are] by their own rules obliged to a strict and religious life. That study [is] fruitful of experiments” (p121). This sounds like a Hindu guru talking about siddhis.

Further observations by White on that theme are:

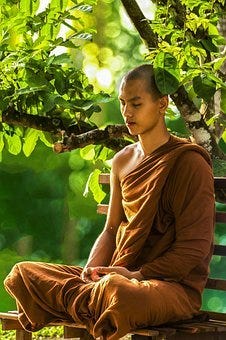

- “It is clear that what the alchemist was engaged in was an odd combination of modern chemistry with a strong element of mysticism and spirituality which, to the twentieth-century mind, appears irrational. To us it seems odd that the esoteric aspect of the alchemist’s efforts and beliefs were to him the most important” (p 126).

- “The spiritual element of the experiment was in fact the key to the true alchemist’s philosophy” (p 127).

- “It was the practical process that was in fact the allegory and their search was really for the elixir of the philosophers’ stone within them: that, by conducting a seemingly mundane set of tasks, they were following a path to enlightenment — allowing themselves to be transmuted into ‘gold’. This is why the alchemist placed such importance on ‘purity of spirit’ and spent long years in preparation for the task of transmutation before so much as touching a crucible” (p 127).

- “The genuine alchemist was absolutely firm in his belief that the emotional and spiritual state of the individual experimenter was involved intimately with the success or failure of the experiment… placed inordinate importance upon this element of his work” (p 128).

- “The adept had to be pure of soul” (p 129).

- “By becoming spiritually involved with a ‘divine’ process, the alchemist believed he could share in its divinity” (p 133).

Along similar lines, Gale Christianson, my other source⁵, writes of “the rise of an esoteric or mystical inner alchemy credited by its practitioners with a power even more wonderful than that of physical transmutation. It was believed that the ingestion of the Elixir of Life… would bestow earthly immortality on its discoverer, provided, of course, he had deported himself in a manner ‘pleasing in the sight of God’. Thus for the esoteric alchemist the transmutation of metals, became a mere symbol of the far more profound transformation of sinful man into a creature worthy of Divine grace” (p 206).

He makes this further observation about the alchemist, strikingly in accord with the spiritual cosmology described above: “Beginning at the outmost layer of a body, he attempted to penetrate to the innermost, invisible, seedlike core. He believed that at this core rested the ‘philosopher’s mercury’, the first matter of all metals and the source of all activity in the universe” (p 227), in other words “the prima materia or first matter from which all substances are formed” (p 231).

Thus the alchemist, with his spiritually developed consciousness, is attempting to reach back to a very high level of existence, prior to all material manifestation. From there it should be genuinely possible to manipulate the formation and transmutation of matter. In Christianson’s words: “To liberate this special mercury from its fixed form in metals would not only open wide the doors to transmutation and the conquest of disease but would make it humanly possible to understand the very process by which God actively sustains and governs all creation, to identify that supreme interface where matter and spirit meet”.

So that’s how they do it! It hardly needs saying that this would be an extremely arduous task, not for the faint-hearted.

In the next article, I’ll discuss some examples of possibly successful alchemy.

Footnotes:

1. Quercus, 2010

2. adapted from his chapter 1, p 29–40

3. Yoga In Practice, David Gordon White and Dominik Wujastyk, Princeton University Press, 2012, p 34

4. Isaac Newton: The Last Sorcerer Fourth Estate, 1998

5. In the Presence of the Creator: Isaac Newton and His Times The Free Press, 1984